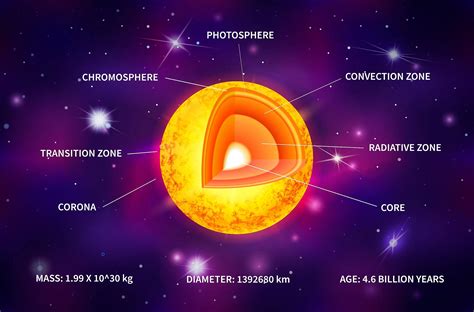

The sun, the star at the center of our solar system, is a massive ball of hot, glowing gas. Its layers are the key to understanding its structure and function. The sun's layers are divided into several distinct regions, each with its own unique characteristics and roles to play in the sun's overall operation. In this article, we will delve into the different layers of the sun, exploring their composition, temperature, and significance in the sun's energy production and overall life cycle.

Key Points

- The sun's core is the hottest part of the sun, with temperatures reaching over 15 million degrees Celsius.

- The radiative zone is the layer where energy generated by nuclear reactions in the core is transferred through radiation.

- The convective zone is the layer where energy is transferred through convection, with hot plasma rising to the surface and cooler plasma sinking.

- The photosphere is the sun's visible surface, emitting the light and heat that we receive on Earth.

- The chromosphere is the layer above the photosphere, visible during solar eclipses as a pinkish-red glow.

- The corona is the outermost layer of the sun, extending millions of kilometers into space.

The Core

The core is the central region of the sun, making up about 25% of its radius. It is here that the sun’s energy is produced through nuclear reactions, specifically the proton-proton chain reaction. This process involves the fusion of hydrogen atoms into helium, releasing vast amounts of energy in the form of light and heat. The core is incredibly hot, with temperatures reaching over 15 million degrees Celsius. This heat energy is what drives the sun’s other layers, powering its activity and influencing the surrounding space.

Nuclear Reactions in the Core

The nuclear reactions that occur in the sun’s core are the result of the intense heat and pressure found in this region. These reactions involve the combination of hydrogen nuclei (protons) to form helium nuclei, releasing energy in the process. The energy released is in the form of gamma rays, which are then transferred to the surrounding plasma, heating it up. This process is not only the source of the sun’s energy but also the reason for its stability, as the outward pressure generated by these reactions balances the inward pull of gravity.

The Radiative Zone

Surrounding the core is the radiative zone, a layer where energy generated by nuclear reactions in the core is transferred through radiation. This zone extends from the core to about 70% of the sun’s radius and is characterized by the absorption and re-emission of photons. As photons travel through this layer, they are constantly being absorbed and re-emitted by the surrounding plasma, gradually making their way outward. This process is slow, taking thousands of years for energy to move through this zone, due to the constant absorption and re-emission of photons.

Energy Transfer in the Radiative Zone

The transfer of energy in the radiative zone is a complex process, involving the interaction of photons with the plasma. Photons emitted by the core travel through the radiative zone, being absorbed by atoms and ions, which then re-emit them at slightly longer wavelengths. This process continues, with the energy being slowly transferred outward. The radiative zone plays a crucial role in the sun’s energy production, as it is here that the energy generated by nuclear reactions is first transferred to the outer layers of the sun.

The Convective Zone

Beyond the radiative zone lies the convective zone, a layer where energy is transferred through convection. This zone extends from the radiative zone to the sun’s surface and is characterized by the movement of hot plasma rising to the surface and cooler plasma sinking. This process is driven by the heat from the radiative zone, causing the plasma to expand and rise. As it reaches the surface, it cools, becomes denser, and sinks back down, creating a cycle of convective circulation. This zone is responsible for the sun’s granular appearance, as the rising and sinking plasma creates cells of hot and cool material.

Convective Processes

Convection in the sun’s convective zone is a critical process, as it is the primary means by which energy is transferred to the sun’s surface. The rising and sinking plasma creates a complex pattern of circulation, with hot material rising to the surface and cooler material sinking. This process is not only important for the sun’s energy production but also influences the sun’s magnetic field and activity. The convective zone is also where the sun’s differential rotation is most pronounced, with the equator rotating faster than the poles.

The Photosphere

The photosphere is the sun’s visible surface, the layer that we can see and from which light and heat are emitted. This layer is about 500 kilometers thick and is the source of the sun’s visible light and heat. The photosphere is the layer where the sun’s energy, generated by nuclear reactions in the core and transferred through the radiative and convective zones, is finally emitted into space. The temperature in the photosphere is about 5500 degrees Celsius, which is the temperature of the light we receive from the sun.

Structure of the Photosphere

The photosphere is composed of granular cells, each about 1000 kilometers in diameter, which are the result of the convective processes in the convective zone. These cells are regions of hot, rising plasma surrounded by cooler, sinking plasma. The photosphere is also where the sun’s magnetic field is most visible, with magnetic field lines emerging from the surface and influencing the surrounding plasma. The photosphere’s structure and dynamics play a crucial role in the sun’s activity, influencing the formation of sunspots, flares, and other phenomena.

The Chromosphere

Above the photosphere lies the chromosphere, a layer that is visible during solar eclipses as a pinkish-red glow. This layer is about 2000 kilometers thick and is characterized by a temperature increase with altitude, reaching temperatures of about 20,000 degrees Celsius. The chromosphere is the layer where the sun’s ultraviolet and X-ray emission is produced, and it plays a critical role in the sun’s activity, influencing the formation of solar flares and coronal mass ejections.

Temperature and Composition of the Chromosphere

The chromosphere’s temperature increase with altitude is due to the absorption of ultraviolet radiation from the photosphere, which heats the plasma. The chromosphere is also characterized by a complex structure, with spicules and fibrils forming a network of hot, dense plasma. The chromosphere’s composition is similar to that of the photosphere, with the addition of emission lines from ions such as calcium and helium. The chromosphere’s dynamics and structure are closely tied to the sun’s magnetic field, influencing the formation of active regions and the sun’s overall activity.

The Corona

The outermost layer of the sun is the corona, a region of hot, tenuous plasma that extends millions of kilometers into space. The corona is visible during solar eclipses as a white glow surrounding the sun and is characterized by temperatures of over 1 million degrees Celsius. The corona is the source of the solar wind, a stream of charged particles that flows away from the sun and influences the surrounding interplanetary space.

Structure and Dynamics of the Corona

The corona’s structure is complex, with streamers and prominences forming a network of hot, dense plasma. The corona is also characterized by a dynamic magnetic field, with magnetic field lines emerging from the surface and influencing the surrounding plasma. The corona’s temperature is due to the release of energy from magnetic reconnection events, which heat the plasma to incredibly high temperatures. The corona plays a critical role in the sun’s activity, influencing the formation of solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and the solar wind.

| Layer | Thickness | Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| Core | about 25% of sun's radius | over 15 million degrees Celsius |

| Radiative Zone | about 70% of sun's radius | about 7 million degrees Celsius |

| Convective Zone | about 30% of sun's radius | about 2 million degrees Celsius |

| Photosphere | about 500 kilometers | about 5500 degrees Celsius |

| Chromosphere | about 2000 kilometers | about 20,000 degrees Celsius |

| Corona | extends millions of kilometers into space | over 1 million degrees Celsius |

What is the hottest part of the sun?

+The hottest part of the sun is its core, with temperatures reaching over 15 million degrees Celsius.

What is the sun's corona?

+The corona is the outermost layer of the sun, extending millions of kilometers into space. It is characterized by temperatures of over 1 million degrees Celsius and is the source of the solar wind.

What is the difference between the radiative zone and the convective zone?

+The radiative zone is the layer where energy is transferred through radiation, while the convective zone is the layer where energy is transferred through convection. The radiative zone is slower and more efficient, while the convective zone is faster and more turbulent.

What is the photosphere?

+The photosphere is the sun's visible surface, the layer that we can see and from which light and heat are emitted. It is about 500 kilometers thick and has a temperature of about 5500 degrees Celsius.

What is the chromosphere?

+The chromosphere is the layer above the photosphere, visible during solar eclipses as a pinkish-red glow. It is about 2000 kilometers thick and has a temperature of about 20,000 degrees Celsius.

Meta description: “Explore the sun’s layers, from the core to the corona, and discover the processes that power our star. Learn about the sun’s structure, energy production, and activity, and gain a deeper understanding of our solar system’s center.”